Keyword searches as a Web command line

Andre’s mentions dumping Google Chrome because of lack of extension support, especially Ubiquity, and lists 15 useful Ubiquity commands.

If you haven’t seen Ubiquity, you should. It’s a great extension that transforms your browser into an Internet command prompt. It is modelled on the Enso Launcher, which is a great piece of work by itself.

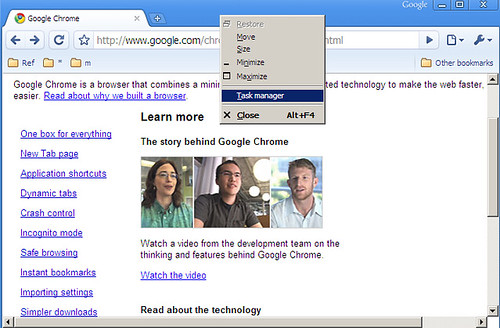

I wasn’t quite prepared to let go of Chrome that easily. On Task Manager, seeing 10 Chrome processes, the largest of which takes up 60MB, is a lot more comforting, psychologically, than 1 Firefox process taking up 300MB. (I rarely hit my 1GB RAM limit, so it shouldn’t matter either way. Yet, the spendthrift in me keeps watching.)

So the question is, can I do all the items on his list without using Ubiquity?

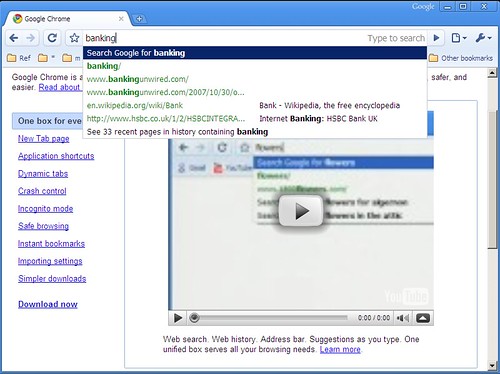

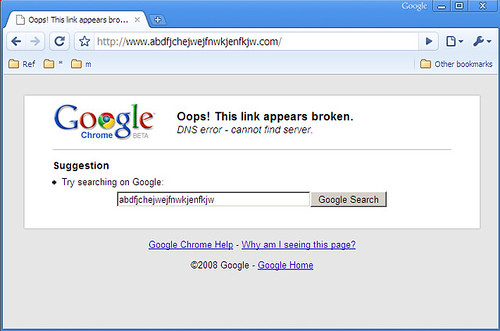

Let’s pick the easiest. Google search. If you typed "g some words" on Ubiquity, you get the Google search results for "some words". But you already have that. If you have Firefox, typing any words on the address bar automatically does a Google search for you. On Internet Explorer, it search live.com, but you can easily change that by installing the Google Toolbar.

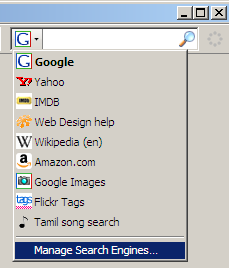

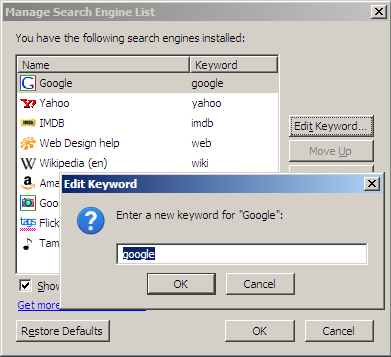

But the great thing is that this can be customised. On Firefox, click on the down arrow icon next to the search box and select "Manage Search Engines…" to see a list of your search engines. Select the one you want to use, click on "Edit Keyword…" and select the keyword you want. For instance, I’ve typed "google".

So when I type "google some words" on the address bar (not the search bar, the address bar) I get search results for "some words". These are called keyword searches.

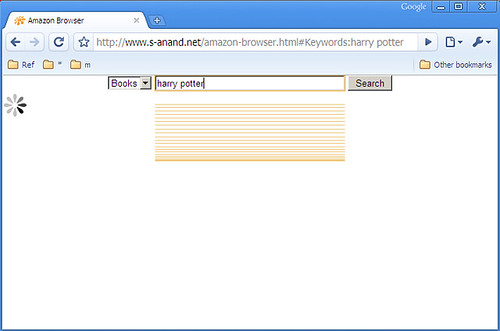

On Firefox, you add your own search engines, but you do that using bookmarks. Press Ctrl-Shift-B (Organize Bookmarks) and create a New Bookmark. You can type in any URL in the location field. If you type "%s" as part of the URL, that will be replaced by the search string. So for instance, using a location http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:Search?search=%s and the keyword "wiki" will do a Wikipedia search for "Harry Potter" if you type "wiki Harry Potter" on the address bar.

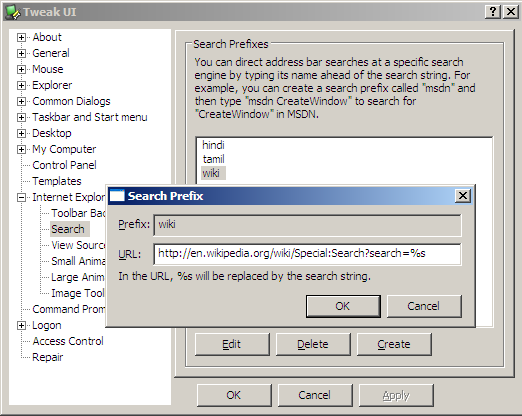

It works on Internet Explorer as well, even with version 6. The easiest way is to download TweakUI. Go to Internet Explorer – Search. Click on the Create button. Type in a keyword (called Prefix) and a URL. If you type "%s" as part of the URL, that will be replaced by the search string.

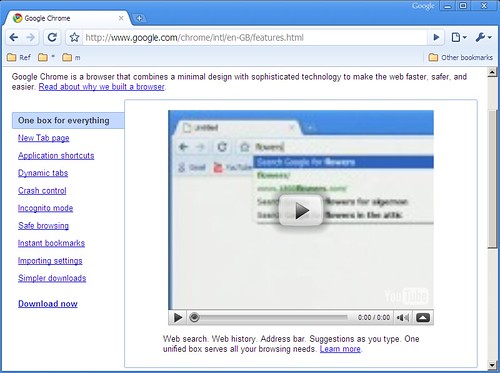

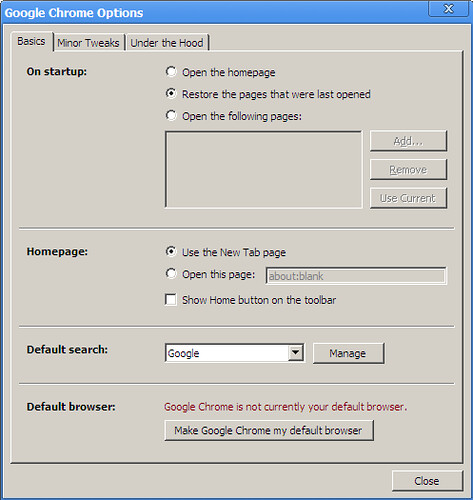

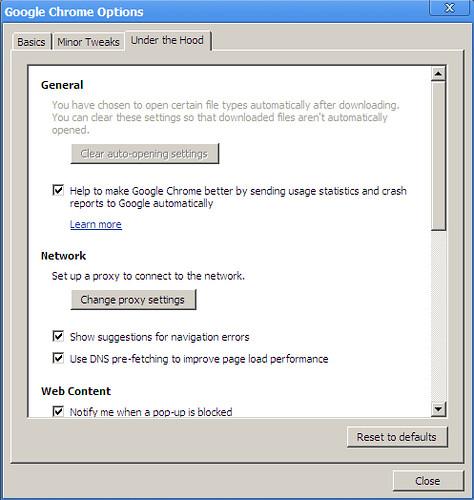

On Google Chrome, get to the Options (what, no shortcut key?) and in the Basics tab, click the Manage button. Here, you can click on "Add" to add a search engine.

So that takes care of all the basic searches: Google, Amazon, IMDB, Wikipedia, etc.

Can we go further? Item 8 on the list caught my attention:

Twit. As much as I love full-featured Twitter clients like TweetDeck, nothing beats the simplicity of hitting Ctrl-Space and typing twit [message] to so_and_so, or sending a selection of text using twit this to so_and_so. At the moment, there’s no way to receive tweets or ping Twitter for new messages.

I don’t use Twitter, but I do use Identi.ca, and I would like something like this. Right now, I’m using Google Talk to update identi.ca. Two problems. I don’t like chatting, and logging on exposes me to a lot of distraction. Secondly, I’d rather not have to open an application just for this. Something in the browser would be perfect. But is it possible?

Identi.ca (and Twitter, and most micro-blogging services) let you update via e-mail. So if I could write a program that would mail identi.ca, I should be done. So I did that with a Perl script.

my $q = new CGI; open OUT, "|/usr/sbin/sendmail -t"; print OUT join "\n", "From: my.authenticated.id@gmail.com", "To: 1234567890abcdef@identica.com", "Subject: \n\n", $q->param('q'); |

So if I placed this at www.s-anand.net/identica (no, I haven’t placed it there), I just need to create a keyword search with a prefix Tidentica" that points to www.s-anand.net/identica?q=%s. Then I can type "identica Here is a message that I want to post" on the address bar, and it gets posted.

Actually, if you can write your own programs, the possibilities are endless. If you’re looking for someone to host this sort of thing for free, Google’s AppEngine may be a reasonable point to start.

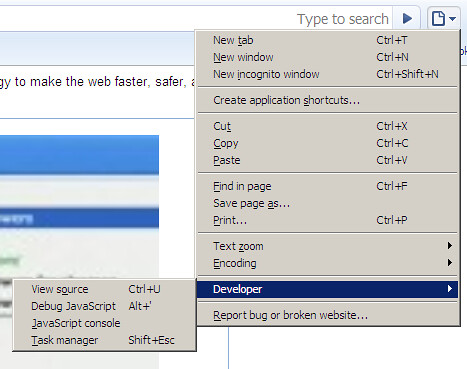

But the real power of this comes with Javascript. Those URLs that you saw for keyword searches? Those can be Javascript URLs. So item 9 on the list…

Word count. As a student of copywriting, I’m frequently curious about an article’s word length. Highlighting the desired text and entering word count into Ubiquity will give you just that.

… might just be possible.

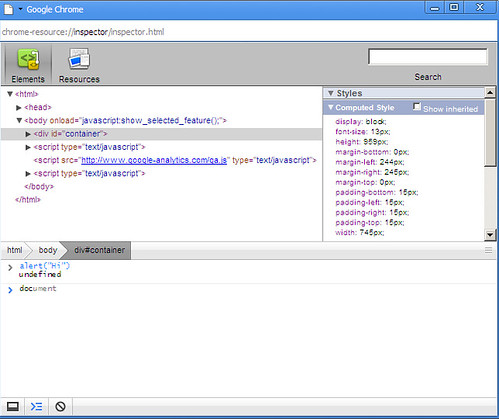

It’s easy to get the selection. The following snippet gives you the current selection. (Tested in IE 5.5 – 8, Firefox 3 and Google Chrome. Should work for Opera, Safari.)

document.selection ? document.selection.createRange().text : window.getSelection ? window.getSelection().toString() : "" |

To get the word count, just split by white space, and count the results:

s = document.selection ? document.selection.createRange().text : window.getSelection ? window.getSelection().toString() : ""; alert(s.split(/\s+/).length + " words") |

Now, this whole thing can be made into a keyword search. Let’s call it count. If I go to the address bar and type "count it", I want to use count the words in the selection. If I typed "count some set of words here", I want to count the words in "some set of words here". Here’s how to do that.

javascript:var s = "%s"; if (s == "it") { s = document.selection ? document.selection.createRange().text : window.getSelection ? window.getSelection().toString() : ""; } alert(s.split(/\s+/).length + " words"); |

Now, put all of this in one line and add it as your keyword search. Try it!

(Note: You need to replace { curly braces } with %7B and %7D in Google Chrome. It interprets curly braces as a special command. Also, Chrome replaces spaces with a +, so the word count will always return 1 if you search for "count some set of words here".)

You could use selections to search as well. If you wanted to Google your selection, just use:

javascript:var s = "%s"; if (s == "it") { s = document.selection ? document.selection.createRange().text : window.getSelection ? window.getSelection().toString() : ""; } location.replace("http://www.google.com/search?q=" + s) |

Typing "google it" will search for your selected words on Google. "google some words" will search for "some words" on Google.

I’ve configured these keyword searches on my browser to:

- Share sites. Typing "share google" adds the page to Google Reader, "share delicious" posts it to del.icio.us, "share digg" diggs the page, etc.

- Send mail from the address bar. Typing "mail someone@gmail.com sub:This is the subject. Rest of the message" in the address bar will send the mail out. (Of course, you need to have created a mail gateway. I’ll try and share this shortly.)

- Add entries to my calendar. Typing "remind Prepare dinner at 8pm" adds a reminder to my calendar to prepare dinner at 8pm.

- Highlight parts of a page. Typing "highlight it" highlights what I’ve selected on the page. Even after I remove the selection, the highlighting stays. Typing "highlight some phrase" highlights all occurrences of "some phrase" in the entire document. The colours change every time you use it on a page, so you can search for multiple words and see where how they’re distributed.

- Replaces tables with charts. Typing "chart it" with a table selected replaces the table with a chart. Typing "chart it as pie" or "chart it as scatter" changes the chart type.

You could actually take any bookmarklet and convert it into a keyword search. Which means that practically anything you can do on Javascript can be convert into a command-line-like syntax on the address bar.

So there it is! You can pretty much have a web command line. I wonder if we could add UNIX-pipes-like functionality.

Keyword searches as a Web command line Read More »